The Life and Works of Professor Mohammad Abdul Jabbar, Chapter Two.

Introduction

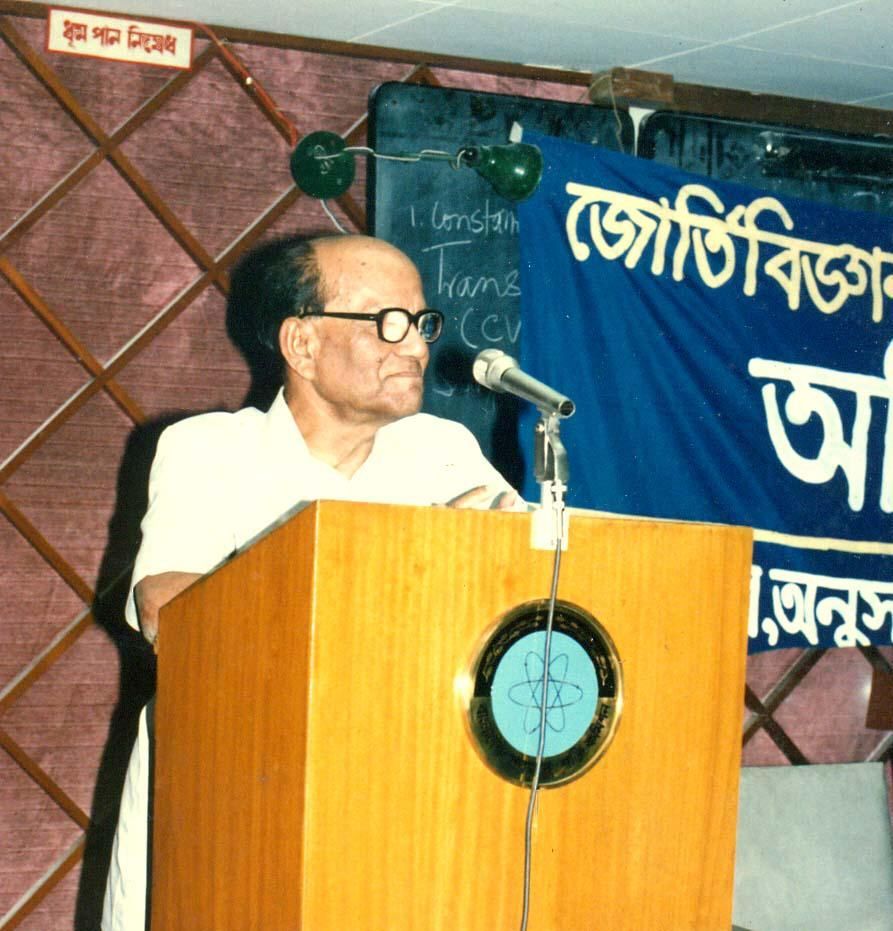

Professor Mohammad Abdul Jabbar was the pioneer in the practice of astronomy in Bangladesh. Long before the independence of Bangladesh in 1971, he started practicing astronomy alone.

He was born in 1915, to Mr Munshi Miazan Mallik, and Mrs. Bulu Begum. He had 5 siblings; 3 brothers and 2 sisters. Professor Abdul Jabbar was the youngest among the brothers and with just one sister younger than him.

Professor Jabbar's elder brother, Mr. Mohammad Akbar Ali shared some history in a journal article in Mahakash Barta, an astronomical journal published by the Bangladesh Astronomical Association (BAA). He wrote,

“Our parents were very poor. We had no land whatsoever. Our father used to say that in his early life he lived across the Padma river. They had a big family and owned a large amount of land in the area. All their lands were lost in the erosion of the Padma river.

As a result of this erosion, the family was dispersed and scattered in present-day Faridpur and Pabna, Bangladesh, as well as the Nadia district in India, all on the eastern banks of the Padma river.

Our father used to say that in his bachelor life, he had to demolish their old house and build a new one 26 times. It may be an exaggeration, but not impossible. Due to river erosion in the country at the time, erosion would cause the river banks to get closer and closer to the riverside houses. However, people generally did not move very far. They would relocate a few metres away, either moving or rebuilding their house accordingly.

This has been a historic issue across many countries, and the reason for it, is that the occupants of the house own the land. If they were to move somewhere else, they'd have to purchase a new plot of land. However, who'd buy their existing plot of land that was being slowly taken back by Mother Nature via her rivers?

With this in mind, Mr. Mallik (Professor Jabbar's father) eventually moved across the Padma, procured some land and built a house, but lost everything else. Mr. Mallik eventually got married after coming across the river. Our father was very intelligent and self-respecting. Although his father-in-law was wealthy, the Professor did not take any help from him. He had no land of his own, and no intension of working on other’s land. Eventually, he became a boatman and started ferrying businessmen from port to port.”

(Muhammad Abdul Jabbar - My younger brother, M. Akbar Ali, Page-4, Mahakash Barta, Second Year, Eleventh Issue, November, 1993).

Mr. Munshi Miazan Mallik, father of Professor Mohammad Abdul Jabbar

Mr. Munshi Miazan Mallik himself had no formal education. He was a boatman, but whilst ferrying wholesalers' goods from port to port on his boat, he came across many different types of people.

During this time, he learned many things on Islam, including holy writings, details of the Koran, the traditions of the Hadith, the legacy of the Milad, and more. These were all learned by listening to Muslim scholars whilst working on his boat.

Mr. Mallik also learned about the Hindu religion; holy writings, the ancient Itihasa writings of the Rāmāyaṇa and Mahābhārata, as well as traditional folk songs – all by speaking to Hindu scholars.

Mr. Mallik himself was technically illiterate, but was very intelligent and talented. His interest in education grew by seeing the Muslim Mullahs and the Hindu priests reading books in the ports. Having seen this, he realised that he wanted to educate his children. However, the small income as a boatman was not sufficient to cover family expenditure, school fees, and such. Hence, he decided to start a small independent business. He started selling small items from village to village, travelling and carrying his items on foot. His family endured great hardship, but were able to survive on this small income.

Whilst travelling on his boat, Mr. Mallik learned a lot of life skills, shared by those he had met on his journeys. For example, he learned how to detect a fever from a pulse or heartbeat, and how to remove poision from the venomous snakes that inhabited the river Padma. Later in life, Mr. Mallik used this knowledge to help treat the common ailments of the local villagers where he travelled to. As a result of this, he became well-known in the local villages, and was honoured and respected for his knowledge and helpfulness.

In the year 1904, Mr. Mallik and Mrs. Begum welcomed their first son, Mr. Mohammad Abid Ali. A few years later, they welcomed their first daughter, Ms. Abijan Begum. 1911 saw their third child, Mr. Mohammad Akbar Ali. Soon afterwards, they welcomed their fourth child, Ms. Mahiun Begum. His fifth and final child was Mr. Mohammad Abdul Jabbar, born in 1915.

The children of Mr. Munshi Miazan Mallik, early life

Mr. Mallik wanted the best for his children, thinking about their long-term future. Despite living in a small village, he decided that his children deserved a proper education, and set out to do his best to provide this. Despite living in a small village, which had no primary school, he enlisted the help of a local cobbler, named Mr. Nilmoni Rishi, who had been educated. Mr. Mallik made an agreement with Mr. Rishi to educate his elder son, Mr. Mohammad Abid Ali.

Mr. Mohammad Abid Ali, first son of Mr. Mallik.

Mr. Rishi started by teaching Mr. Mohammad Abid Ali the alphabet. Mr. Mallik used to take his son to Mr. Rishi, and then spend his time talking to the other workers whilst Mr. Rishi delivered his lessons to Mr. Rishi. At this time, Muslim society was strongly opposed to any other education than that delivered by an educational institution (a Madrasa). Mr. Mallik also faced further complications because it was unheard of for a Muslim man's son to be educated by a Hindu, let alone a simple cobbler. This created a hostile and unfriendly reaction in the local community; however Mr. Mallik and Mr. Rishi were not bothered by this reaction, and continued young Mr. Mohammad Abid Ali's lessons.

After learning the alphabet, Mr. Mohammad Abid Ali was then admitted to a primary school in another village. The school required a monthly fee of 4 Ānnas. As this was during British India rule, an Ānna was equivalent to 1/16th of a Rupee, the leading currency at the time. However, Mr. Mallik could not afford the monthly fee at the time – but the Headmaster had understood this and had granted Mr. Mohammad Abid Ali a scholarship and stipend at the school.

The Headmaster's name is unfortunately lost in time, but he encouraged Mr. Mohammad Abid Ali to complete his studies and sit the final examinations. Mr. Mohammad Abid Ali ended up passing the examinations, and was accepted to Sujanagar Middle Education School (now known as Sujanagar Model Pilot High School). The tuition fee for Sujanagar was 1 Rupee per month, but Mr. Mohammad Abid Ali's scholarship continued into High School so Mr. Mallik did not need to pay anything for his son's continued education.

Mr. Mohammad Abid Ali was the first scholarship recipient from the entire Pabna district. The stipend was 2 Rupees per month. This scholarship opened the door for educating Mr. Mohammad Abid Ali's two younger brothers too. Mr. Mallik very soon enrolled his other sons, the eldest Mr. Mohammad Akbar Ali and the youngest, Mr. Mohammad Abdul Jabbar, into the village primary school that Mr. Mohammad Abid Ali had attended previously. Their tuition fees were covered by the stipend that their older brother had been granted.

Even at this stage of a fragile peace for Mr. Mallik's children, there were still some differing opinions. Some of Mr. Mallik's friends and family questioned his choices – they said, “you can't even afford to put food on the table, so why are you sending the boys to school?” These comments continued, including further questions such as, “If you really want to, send the older boy to school and the other two can work in someone's house. They'll earn money and you'll get food and clothes too.”

Mr. Mohammad Akbar Ali, second son of Mr. Mallik

Mr. Mallik and Mrs. Begum ignored this criticism. They were determined to continue to educate their children, despite their own hardships.

Whilst Mr. Mallik was dealing with the pressure from the local villages, Mrs. Begum had her own issues to deal with for her boys. One of Mrs. Begum's family members, a Mullah, was insisting that Mr. Mohammad Abdul Jabbar should attend the local Madrasa. The Mullah advised that the Madrasa could offer the education that Mr. Mallik was so keen to instil on his sons, but did not require any tuition fees. The Mullah also advised that the Madrasa could arrange a zaigir, a historic term for a childminder for Mr. Mohammad Abdul Jabbar, to reduce the stress for the parents. However, even at a young age, Mr. Mohammad Abdul Jabbar was a stubborn boy and insisted that he went to school. It took some time, but eventually, his insistency won and he went to school just like his older brothers.

The young Mr. Mohammad Abdul Jabbar had an uneventful few years in school. The scholarship offered to him by his older brother continued through his education, and he passed his examinations successfully. Mr. Mohammad Abdul Jabbar then received his admission into Upper School, along with his own scholarship, which at the time was what the school charged, 3 Rupees per month, for a 3 year course. Between them, their scholarships, and their father's efforts, the brothers were able to achieve the same level of education, going through the same classes as each other. Their scholarships did not only cover their education, but also covered their living expenses too. They were able to afford study materials, such as pen and paper, but also able to afford modest clothing and food. Mr. Mallik would have been proud that his sons were able to look after themselves, after years of being convinced otherwise.

The young boys' education started with Pathshala, a term that has been lost to the ages. This comes from the ancient education system from British India, which eventually became Bangladesh. Pathshala classes are held underneath lofty trees, to create learning spaces without walls, but with open skies and unending horizons.

Whether Mr. Mallik's love of the rivers, and the horizon past the bow of his boat, was something his children inherited a love of, we will never know. However, his sons very happily finished their education in the Pathshala stage, and then moved on to Middle Education, Higher Education, and then onto College and University. As the young boys could not afford to buy new textbooks, they relied on older textbooks to continue their education.

The children of Mr. Munshi Miazan Mallik, further education & adulthood

Professor Mohammad Abdul Jabbar studied at Satbaria High School. Whilst attending the school, he also used to publish handwritten newspapers along with his friends, which would eventually lead to his interest in writing and publishing. During his studies, a local author (who's name is sadly lost to the ages) was publishing a book, and invited the nearby school and college students to review it. The author offered prizes to the three best journalistic analysis of his book; the young Professor took part and submitted his own analysis, earning himself the second-place prize – even though he was competing with college students older than himself.

It should come as no surprise that the young Professor then passed his final school exams with excellent results, and was granted his scholarship to The Presidency University (which, at the time, was also a college). The Professor's love of writing continued and whilst studying at The Presidency, he began writing more in-depth articles to explain more complex topics to children. He mainly focused on science, but by this time he did not need to hand-write his own school newspapers. The commercial publications Azad (আজাদ)and Mohammadi (মোহাম্মদী), along with some others, published his articles as part of their newspapers.

Whilst the young Professor was studying for his college qualifiactions, his elder brother, Mr. Mohammad Akbar Ali, was studying for his MSc (Hons) in Chemistry. He graduated in 1933 with a first-class degree, and had the second-highest examination results amongst his peers. He was a preferred student of Dr. Muhammad Qudrat-i-Khuda, who at the time was his Lead Professor and was also the Head of Chemistry at The Presidency University.

Having gained his Doctorate from the University of London in 1929, Dr. Muhammad Qudrat-i-Khuda continued to educate students at The Presidency University, but also served as the President of the East Pakistan Academy of Sciences, as Bangladesh was known at the time. He then served as the Chairman of the National Education Commission once Bangladesh had gained it's independence. He then founded the Bangladesh Council of Scientific and Industrial Research.

For Mr. Mohammad Akbar Ali to be a preferred student of such a distinguished individual must have been a proud achievement, which evidently spurred his younger brother to follow in his footsteps.

The young Professor Mohammad Abdul Jabbar desired to pursue what his elder brother had accomplished, by focusing on Chemistry, even going so far as to pick the subject for his own MSc (Hons) degree.

Unfortunately, the young Professor did not do as well as he had wanted in Chemistry, but his Mathematics skills were exemplary. Dr. Muhammad Qudrat-i-Khuda, having supported his elder brother, offered some personal advice to the young Professor. The advice given was to continue to pursue a degree, but in Mathematics, rather than Chemistry.

The young Professor listened to Dr. Muhammad Qudrat-i-Khuda and started his BSc (Hons) in Mathematics at The Presidency University. A few uneventful years passed, and the young Professor graduated with his BSc (Hons) in Mathematics.

Once the young Professor had graduated, he received a letter from Kolkata University. They had just welcomed a new German professor called Professor Friedrich Wilhelm Levi, and he had personally requested that Professor Mohammad Abdul Jabbar enrol on a new course the university was offering – an MSc (Hons) in Pure Mathematics. Professor Levi himself had received his Doctorate from a pioneer in algebraic geometry, and had received an Iron Cross during his service in the German Army.

Whether or not Dr. Muhammad Qudrat-i-Khuda had any influence on this personal invitation, we will sadly never know.

The young Professor gladly accepted the invitation and commenced his MSc (Hons) studies. As per his undergraduate studies, the years were uneventful and in 1938, he graduated with a first-class degree, with the highest grade amongst his peers. The young Professor was also the first Muslim student to obtain a first-class MSc (Hons) in a mathematical subject. A historic anecdote mentions that “he did not let Professor Friedrich Wilhelm Levi” down, so it can be expected that the tutor and student worked well together and had a healthy respect for each other.

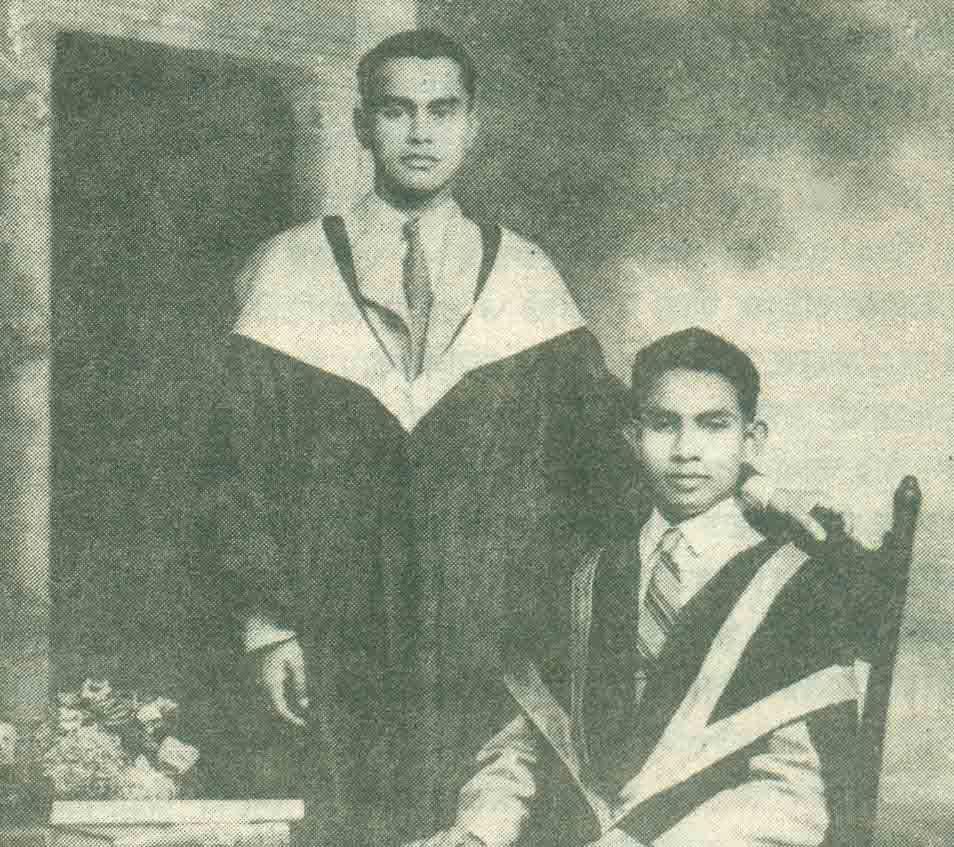

The young Professor with his elder brother.

Mohammad Abdul Jabbar MSc (Hons) – Further Education & World War II

As the young Professor completed his Masters degree, thoughts turned to where he would go next. At the time, Cambridge University had a highly-acclaimed Tripos degree course which some of the young Professor's elders perceived to be a natural step forwards.

Professor Levi, however, did not agree. He had seen the potential that the young Professor had; since the Tripos degree was just an Honours degree, the next step would be to pursue a DSc (Doctorate in Science). The young Professor had an enormous amount of respect and a lot of faith in Professor Levi's advice, so, with his blessings, the young Professor enrolled on a DSc programme at Cambridge University, and as air travel was not as accessible as it is in modern times, he boarded a passenger ship bound for London.

He embarked on his journey on 1 September 1939. His scholarship status followed him too, and he would be joining Cambridge University on a full scholarship.

The effects of war can trickle down to individuals and areas that one would never expect. Two days after the young Professor set sail for the United Kingdom, on 3 September 1939, Britain had entered World War II by invading then-Nazi Germany. The ship that the young Professor was travelling on sailed under a British flag, and given the instability at the time, the Captain of the ship elected to avoid the Suez Canal (in Egypt), to reduce the risk of being attacked by German ships, U-boats, or similar. Instead, the ship was navigated around Africa, adding an additional 5,100 miles (6,200 km) and an extra 45 days to the journey time.

Ships in 1939 did not have the luxuries afforded to modern cruise ships, let alone the restrictions that war brings. The young Professor's journey was not only 45 days longer than expected, but due to the limited supplies on board for such an extended journey, the Captain had to ration the meagre supplies that remained. By the time the young Professor reached the United Kingdom, the ship had depleted its food supplies and had been suffering a severe water shortage. Those on board were limited to one single glass of potable water per day.

This did not stop the young Professor. After disembarking the ship, he eventually confirmed his enrollment to Cambridge University, initially for an MSc degree but with the intention to elevate to a DSc degree as soon as possible, given the global war that was prevalent at the time.

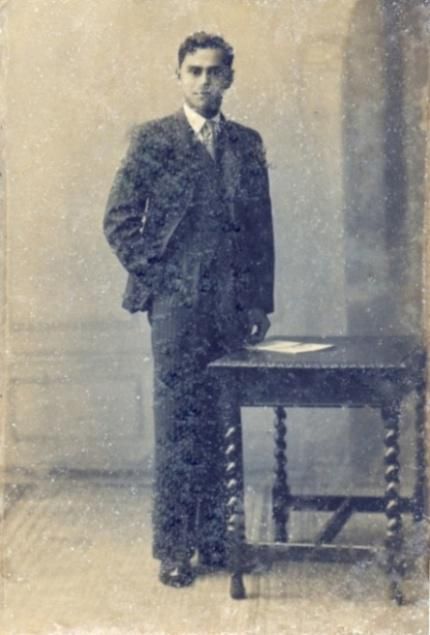

Mohammad Abdul Jabbar MSc (Hons), in his early days at Cambridge University.

Whilst the young Professor was trying to settle into his studies, having left his loved ones behind, World War II escalated. The young Professor continued to do his best as a student, eventually getting accepted onto the DSc programme. His new supervisor, who's name is also sadly lost to the ages, pushed for the University to continue the young Professor's education – however, sadly the supervisor was conscripted to the British Army. Furthermore, the British government decided that under wartime protocols, any non-permanent foreigners could act as spies for British military operations, so they elected to remove all of these foreign men and women and send the back to their originating countries. The young Professor was part of this.

Professor Levi had remained in Kolkata and when the young Professor returned, he was welcomed back to the university to continue his research, working under Professor Levi. The young Professor also started part-time lecturing at Kolkata University, continuing his studies and lecturing until 1943. During this time, he and Professor Levi attended various mathematical seminars across India, and the two even published some academic papers together.

Whether or not it was part of the global war, the Hindu-Muslim conflict was also reaching it's peak in 1943. At the same time, Professor Levi's older sister, Franziska Fitting (née Levi) was sadly killed during the Holocaust. Professor Levi took a break from teaching at this time, vacating his lecturer role. Due to the Hindu-Muslim conflict, the young Professor was not allowed to fill the shoes of his mentor and lecturer at the university.

The young Professor decided to take matters into his own hands, and moved to Chittagong College as a lecturer. He eventually returned to the Presidency College as a lecturer, transferring over. Sadly Professor Levi, whilst remaining in British India for a few years, was no longer part of the story of Professor Mohammad Abdul Jabbar.

Professor Levi was a mentor, a friend, an inspiration to the young Professor. Whilst he is no longer part of the story, Professor Levi's grandchildren continue to be active in politics and (some of) the subjects of the man that Professor Mohammad Abdul Jabbar respected so highly.